About my Dad

George Hatsopoulos (1927-2018)

[Musical Inspiration: Kyra Giorgena, George Dalaras]

George Hatsopoulos had big dreams when he was a teenager during the Nazi occupation of Greece. At that time, trucks drove through Athens picking up bodies of people who had died of hunger, and every time a Nazi soldier in Greece got killed, fifty random Greeks were executed. When two Nazi officers came to live in half of my father’s house, they sealed the dials of the four radios to transmit only the German station, and they said that if the seals were broken, the family would be killed. Despite this, and unbeknownst to his parents, my dad built radios in his basement for the Resistance while the German soldiers lived upstairs.

Later, instead of accepting a cushy position for which he was being groomed by his family, he set out for America. As a professor at MIT, his contribution to science was restating, with Keenan, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, about equilibrium states. Stable equilibrium—a state in which a body returns to its original position after being disturbed—is a great metaphor for our home life growing up. No matter what challenges my brother Nicho and I faced in the world, home was a safe haven. Even after college, we returned every summer to my parents’ house in Greece. “My Big Fat Greek Wedding” was a funny movie, but it’s no joke. My parents actually bought a plot of land across the street so I could move there after I got married. And I’m pretty sure Walter and I are the only couple I know who spent their honeymoon with the entire extended family.

A less Thermodynamic explanation of equilibrium is that of equal balance between different influences. My mother was nurturing, while my father—modeling through his behavior—pushed us to work hard, through any obstacle, and pursue our passion. These forces from our parents gave us intellectual and emotional balance, as did their marriage, which was one of the best relationships I have ever witnessed.

My dad never missed an opportunity to point out a word that comes from Greek, or some historic development that originated in Greece, and he never forgot his Greek identity. At the same time, he was really in love with America, because it was in America where he found the opportunity to drive toward his goals, build and create. As an entrepreneur, he embraced and ultimately embodied the American Dream. He would've been very proud of all the recent startup activity by this new generation in Greece.

My dad had some distinctive traits which he never tried to hide. First, he was a little bit oblivious and scatter-brained. Like me, he forgot everything: birthdays, errands, names, faces, and who knows how many jackets left in taxi cabs. But, unlike me, he never forgot a good meal. He was obsessed with food and would remember decades later the sole meunière in Paris or the burger in Waltham. Having grown up with hunger, he loved fat, like cream in his cereal and a slab of butter on everything.

His mood was in a perpetual equilibrium state. He had a happy, generous spirit, always greeting you with booming enthusiasm. I saw him seriously angry only twice in my life. (Neither incident was my fault!) Kind and gentle, he defied the CEO image you see on TV. Former MIT students, business colleagues at all levels, and recently the baker in Greece, tell stories about how he took time to help them, guide them, or even shape their lives. That he was great is obvious; that he was good is more significant.

He worked all the time, and he loved it. He pursued his intellectual passions with unrelenting effort and joy, demonstrating the importance of following your own unique path in life. He showed us that anything is possible if you try hard enough. He was a clean thinker, very structured and linear, like any good engineer. His gift to us was a conviction that the world made sense and could be understood by the rational mind; that problems could be solved by thinking. At family dinner, which he rarely missed, he would challenge us to figure things out, by making educated estimates. It was this profound faith in logic that added to our sense of equilibrium.

Still, Nicho and I knew to never ask him a quick homework question, because my dad always started with first principles, re-deriving Pythagorus’s Theorem from scratch before working his way through the history of math. And although he advised U.S. presidents and testified before congress about his papers on economic policy, he preferred giving his long lectures to the family, undeterred by our level of interest.

Although he wasn’t the kind of dad to go out and play baseball with us, he took us to Thermo Electron on weekends, where we played with the toy steam engine on his desk and an early computer the size of a suitcase, which had about 8 KB of RAM.

My father was effusive about his love of family, always doling out his sloppy kisses and hugging you in his soft cashmere sweaters. But at home or in Greece, while we were outside playing, he’d be in his study, under a cloud of his cigar smoke, working, dreaming, and analyzing massive spreadsheets which exploded more than one computer.

A profound sense of satisfaction comes from finishing an outstanding novel or hearing the end of a great piece of music, like the final uplifting syllable sung at the end of Mozart's Requiem. Even though it would be delightful if the music never stopped, the perfection and beauty of the work’s completeness is intensely pleasing. I wonder if my father felt that sense of satisfaction about his life, which was something of a fairy tale. I have the sense that he did, because he was very peaceful in his old age. Despite his body and mind betraying him, he was content, agreeable, loving and grateful.

We’ll all miss my father’s larger-than-life presence at the dinner table, where it was often hard to get a word in. We’ll miss his ouzo by the pool after his 3-minute swims, his backgammon, his zombies at Yangtze River, and his continual pressing for us to come back home to visit—even though he’d be in his study working when we got there.

He ran a good race, but his time is up, and what sense can we make of that? He left a legacy in Thermodynamics, Economics and business, but he also left a legacy in what he passed down through me—and my husband Walter, his protégé both at MIT and at Thermo Electron—to our four children. Thomas is an easy, happy spirit, who is intellectually curious, and like his grandfather, does well in school without any stress. Christopher approaches golf with passion, focus and discipline, relishing the challenge and raising his game when the stakes go up. Things come easily to Natasha, as they did to her grandfather, and she’s also a forgetter, of everything from where she left her license to when her homework is due, but she never forgets a meal, taking my father’s food obsession to a whole new level. My dad lost his cognition without witnessing Zoe at MIT, the third generation taking Course 2 and dreaming of doing a startup, learning all about stable equilibrium states and the Second Law of Thermodynamics at the place where his career started, the place where he taught with Walter so many years ago. Our children’s dreams all connect back to my father. So perhaps his race was actually a relay, and it’s time to pass the baton, to give someone else their turn.

The following video was prepared by John Freidah at MIT in his remembrance:

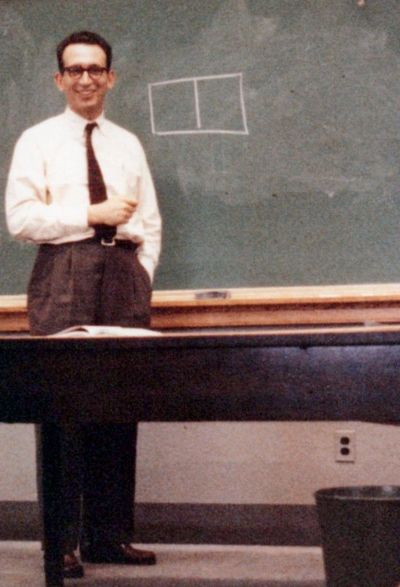

So far, his Thermodynamics problem up on the board doesn't look all that challenging.

This website uses cookies.

Cookies are utilized to analyze website traffic and optimize your experience. By accepting use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.